Intro - Framing the question of intelligence

Artificial intelligence is emerging all around us. The technology has been gradually making its way into the background of everyday products over the past 50 years, until suddenly ChatGPT opened everyone’s eyes to the immense power of the Law of Accelerated Returns. With Silicon Valley VCs and Big Tech alike pouring money into generative AI, in the next few years, we can expect to see the following changes in society:

- Businesses using AI to make quality of life decisions for consumers, including who qualifies for a mortgage and life/death decisions (self-driving cars)

- Jobs being displaced by new occupational roles at a pace we haven’t seen since the Industrial Revolution

- Governments incorporating AI to make decisions in law enforcement, military warfare and the content that gets disseminated into classrooms

Beyond these immediate concerns, a once distant question has become imminent: will AI surpass human intelligence, and if so, what is our purpose in the world? Before we can discuss whether AI will surpass human intelligence, we need to have a common definition of intelligence.

What is intelligence? - The role our body plays

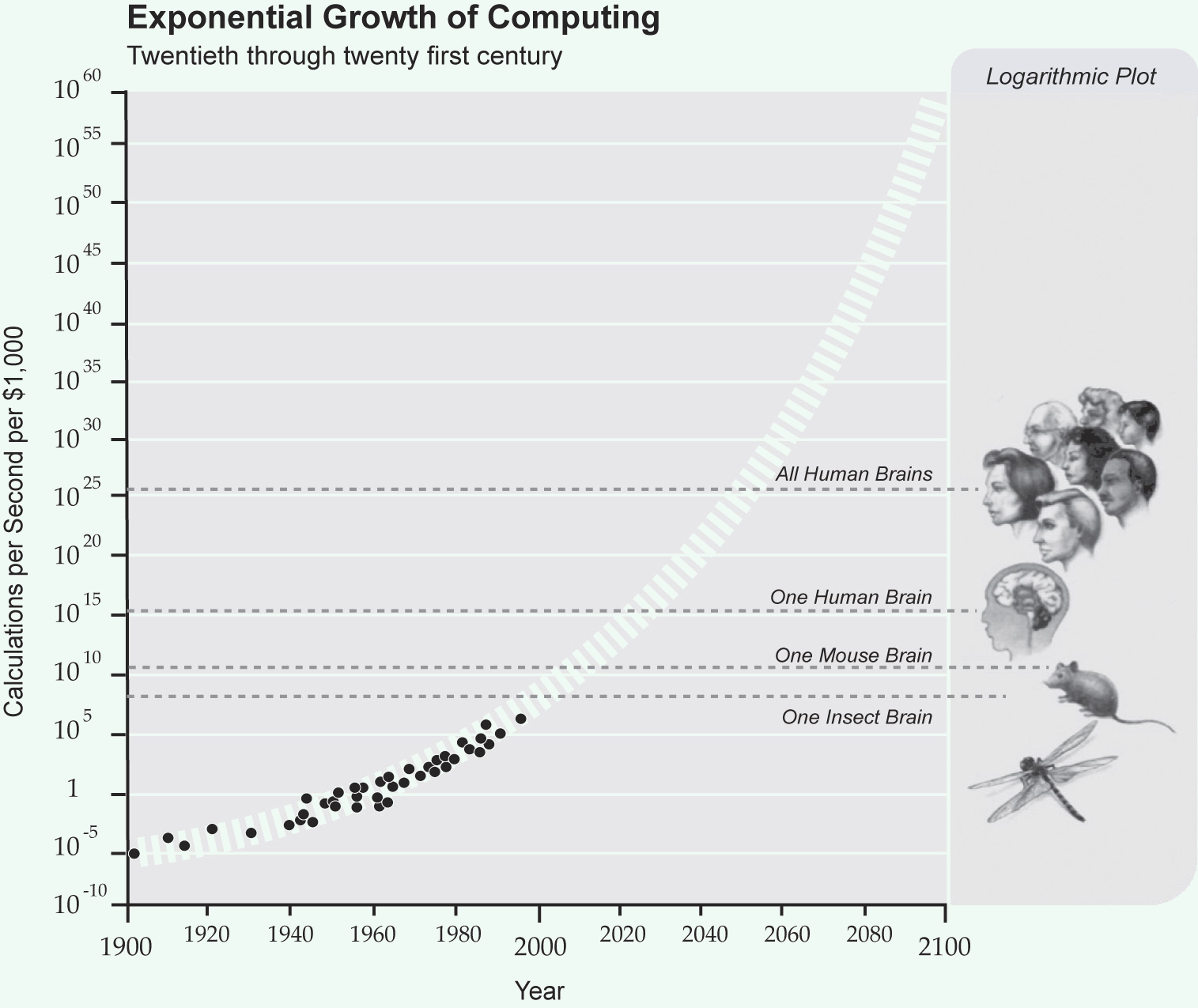

Ask today’s leading scientists and you’ll hear a variety of answers, from solving math problems to scoring highly on standardized tests. A common viewpoint is that the human brain is what gives rise to intelligence, and AI has been modeled off of this premise. The deep learning models that underpin GenAI are based on the concept of neural networks, inspired by how neurons in the brain form connections. As the thinking goes, the human brain is limited in physical capacity, whereas a digital neural network can scale infinitely, which will eventually result in a AI gaining superior intelligence. If we solely look at compute power, this makes for a compelling argument.

But this assumes that modeling our brain, separate and apart from our body, is sufficient to replicate our intelligence. We will now challenge this assumption.

In order to do this argument justice, we would have to consider what it would be like to have a brain but to have never had a body; but the best we can do is imagine what it would be like to lose our current body, which unfortunately is not the same thing. We would still be considering intelligence with the benefit of having had a body for an entire lifetime. This conceptual gap makes questioning the role our body in intelligence deceptively challenging. It is also core to the problems underlying misconceptions about human vs artificial intelligence.

With this caveat aside, we will try to account for how the body influences the formation of our thoughts by considering the role the nervous system plays in our intelligence.

Intelligence as movement - the nervous system as an extension of the brain

One way to better appreciate the relationship between the body and brain is to reconsider the separation of the brain and nervous system.